Not only was he the absolute genius of the Renaissance and a man centuries ahead of his time, but Leonardo da Vinci is also an authentic made in Italy brand. Painter, sculptor, inventor, scientist, astronomer, architect, engineer, and philosopher, a pioneer in the use of perspective and the depiction of human figures and movement, Leonardo is the personality that best represents Italian wit and creativity. It is no coincidence that the Vitruvian Man, a symbol of talent and innovation, was chosen to represent made in Italy.

Leonardo da Vinci: 10 Things You Don't Know About the Italian genius

To celebrate the Renaissance genius, the man of all-encompassing knowledge who may end up on the new 100 euro banknotes, the inventor of cutting-edge instruments and futuristic machines that anticipated some of the most modern technologies by centuries, here are 10 trivia about little-known but highly debated aspects of the artist and the man. From his education as an omo sanza lettere (an unlettered man) due to his problematic origins to his never-completed masterpiece, from his fierce rivalry with Michelangelo to the astronomical value of the Mona Lisa, the most famous artwork in the world.

Discover Leonardo's Masterpiece: Last Supper in Milan10. When and where was Leonardo da Vinci born

Leonardo was born on April 15, 1452, in Anchiano, a hamlet of Vinci in the province of Florence, at the foot of Montalbano, in the communal and Medici-controlled Tuscany. Today, Vinci is home to some iconic sites: the birthplace in Anchiano, the Leonardian Library (opened in 1928 by Gustavo Uzielli, one of the greatest scholars of the artist and inventor), the sculpture The Man of Vinci by Mario Ceroli, inspired by the famous Vitruvian Man drawing, and above all, the Leonardian Museum, housed between Palazzina Uzielli and the Castle of the Counts Guidi, one of the most extensive and original collections dedicated to the genius.

At the time of his birth in 1452, Vinci was a small village of nobles and peasants. Leonardo was the son of an illegitimate relationship: his father, the notary Piero Fruosino da Vinci, was 26 years old (and had four marriages to his name) when he impregnated Caterina di Meo Lippi, a woman of Caucasian origin who arrived in Italy as a slave, sold and bought multiple times between Constantinople, Venice, and Florence. Freed through a notarial act signed by Piero, Caterina took care of little Leonardo for about ten years with his paternal grandparents before marrying the ceramist Antonio di Pietro Buti del Vacca da Poggio Zeppi, nicknamed "Attaccabriga," and having five more children—four daughters and a son.

9. Unschooled, vegetarian and... charged with sodomy

In the mid-15th century, studying was difficult for the son of a freed slave: Leonardo was an omo sanza lettere, or an unlettered man, as he himself defined it. He did not study Latin or Greek and was not even interested in rote learning. On the contrary, he despised literati who exploited the art and creativity of others. What mattered to Leonardo da Vinci was concrete experience: only by knowing real-world phenomena could one reason, reflect, and face life. A self-taught individual, Leonardo approached art as an apprentice in the workshop of the painter Andrea del Verrocchio. Legend has it that when the master asked him to paint an angel, the student's drawing was so astonishing that Verrocchio decided to stop painting.

Beyond being a man without letters, the universal genius was also a great lover of food and cooking, preferably vegetarian. Though he did not disdain eating meat and fish, Leonardo embraced vegetarianism at many ceremonies and banquets in Florence, Milan, and Amboise. When he bought meat, it was primarily to experiment with recipes, study the effects of fire, and invent mechanisms for the spit-roast. Leonardo's eccentricity has been debated since the 16th century, including his alleged homosexuality. There is an official complaint dated April 9, 1476, accusing him of sodomy with a 17-year-old boy who was a prostitute, Jacopo Saltarelli. However, the judges immediately dismissed the case with the verdict absoluti cum conditione ut retumburentur, leaving Leonardo completely acquitted. As for his sexual preferences, if it even matters, scholars have long been divided.

8. He adored animals

LANBOZ - Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie

Leonardo's presumed vegetarianism was actually due to his great love and respect for animals. The Tuscan artist considered all forms of life sacred and believed the spirit of God was present in all creatures. Throughout his life, he studied and drew countless animals but, more importantly, did everything possible to give them freedom. “And he showed it by often passing by places where birds were sold, taking them out of cages with his own hands, paying the price demanded, and setting them free in the air, restoring their lost liberty,” wrote the painter, architect, and art historian Giorgio Vasari in the biography he dedicated to him.

Leonardo was interested in all animals: mammals, birds, fish, and insects. He wanted to understand how they were born and reproduced, how they grew, and how they managed to run, fly, swim, or jump. He had a particular fondness for horses, which he frequently drew. Animals appear in many of his works, from Lady with an Ermine (actually a ferret) to The Virgin of the Rocks, which features a dog on a leash, interpreted by researchers as “a symbol of man obeying God, the divine commandments, and Jesus.”

7. How did Leonardo da Vinci die

Leonardo died at the age of 67 on May 2, 1519, at the manor of Clos Lucé in Amboise, France. Vasari believed his death resulted from a paroxysmal phenomenon: paralysis of the right hand, then the rest of the body, likely due to what we now consider a stroke. Other scholars, however, suggest that Leonardo suffered from ulnar nerve paralysis, affecting many hand muscles—a neuropathy that deprived him of the use of his right hand.

Leonardo's death was depicted by the French painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres in his 1818 painting La Mort de Léonard de Vinci, with King Francis I embracing the artist to receive his last breath. In his will, drafted a few weeks before his death in front of notary Guglielmo Boreau, his friend Francesco Melzi, and five witnesses, Leonardo requested to be buried in the Church of Saint Florentin in Amboise. His wish was granted, but fifty years later, his tomb was violated, and his remains were scattered amid the religious conflicts between Catholics and Huguenots. Those wishing to visit the tomb of the Florentine genius can do so at the Chapel of Saint-Hubert in the Château d'Amboise, where since 1874, bones attributed to Leonardo have rested.

6. He wrote in reverse

V&A - Victoria and Albert Museum

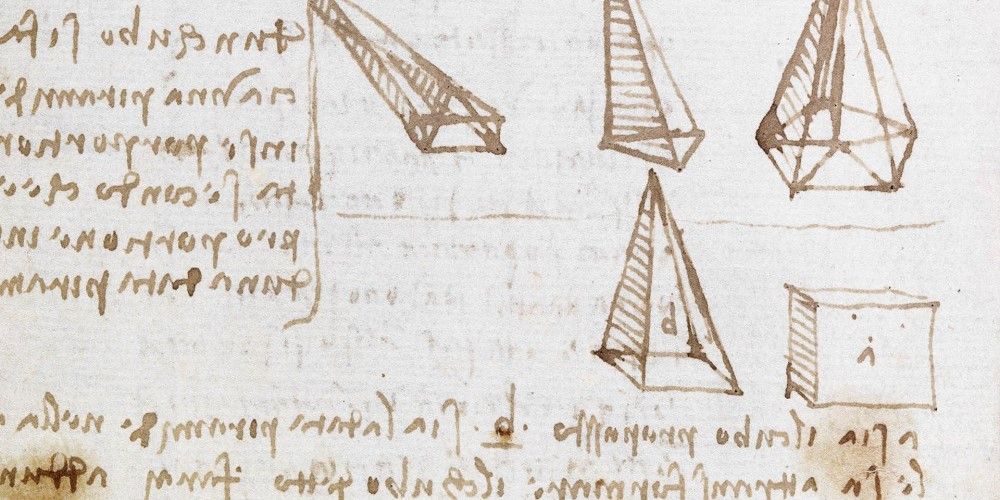

For his entire life, Leonardo loved sitting at his desk, taking pen and paper, and writing letters to his many correspondents: family, friends, students, artisans, artists, politicians, lords, and princes. Over the years, Da Vinci wrote thousands of letters, but for his notes and drawings, he used an unusual mirrored script—writing from right to left, starting from the last page to the first. The reason? Not an attempt to make his work incomprehensible to rivals, but a habit acquired in childhood.

Leonardo is left-handed, and having never received a formal education, as an omo sanza lettere, no one ever corrected his boustrophedon writing style, similar to Arabic and Hebrew, possibly inherited from his Circassian slave mother who arrived in Tuscany from the Caucasus, or from his grandfather Antonio, a merchant who frequently traveled to Morocco and the Maghreb. Some neurologists have even hypothesized that Leonardo was dyslexic and perceived words as figures. Over time, he developed a fixed handwriting style (from left to right), which he reserved for letters and demonstrative cases, such as certain topographical maps.

5. Bill Gates owns his Codex Leicester

The co-founder of Microsoft, a central figure in thousands of conspiracy theories, owns the only copy of the Codex Leicester, an illustrated manuscript dating between 1506 and 1510 and the only one of Leonardo's codices in private hands. Comprising 36 large sheets folded in two to become 18 bifolios, each with four pages, the Leicester, also known as the Codex Hammer, collects Leonardo's writings dedicated to the natural element that fascinated him the most: water. These pages contain notes, theories, dissertations, sketches, drawings, and diagrams on geology, hydraulics, paleontology, astronomy, anatomy, and the formation of rivers and water basins.

Gates purchased the Codex Leicester at auction in 1994 for $30.8 million, less than a tenth of the price of Salvator Mundi, which was auctioned in New York in 2017 for $450.3 million. Initially part of Leonardo's legacy to Francesco Melzi, the work changed hands multiple times: first to sculptor Guglielmo della Porta and painter Giuseppe Ghezzi, then to Thomas Coke, the Earl of Leicester, and American entrepreneur Armand Hammer, from whom it received its various names. Since it is owned by Gates, the only way to access the Leonardo manuscript is through its digitized version on the official website of the British Library. The original has returned to Florence twice: once in 1982 and again in 2018, for exhibitions organized at the Uffizi Gallery.

4. He hated Michelangelo

If not outright hatred, there was at least a significant rivalry between the two artists due to their opposing personalities: Da Vinci was seductive, elegant, and worldly, whereas Michelangelo was reclusive, unkempt, and devoted to work. Leonardo often said that Michelangelo's sculpted figures had muscles resembling “sacks of walnuts or bunches of radishes.” Michelangelo retorted that Leonardo was influenced by “those Milanese capons,” referring to the hard-headed Lombards. This artistic feud between opposites who despised each other culminated in a rare street encounter in Florence, where they engaged in a heated, insult-filled confrontation.

Poet, playwright, and writer Roberto Mercadini describes them as “genius and darkness.” When Leonardo joined the commission of artists tasked with deciding the placement of Michelangelo's masterpiece, David, he was less concerned with its location (suggesting it be placed under a niche in the Loggia instead of Piazza della Signoria) and more focused on criticizing the poor quality of the marble used. Two opposing visions of art and life, a rivalry fueled by envy and competition, ultimately contributed to the sublime heights of the Italian Renaissance.

3. What is Leonardo da Vinci's favorite color?

Some scholars argue that pink and red were Leonardo's favorite colors. Behind this choice lies not just an artistic but also a personal motivation: far from being universally admired as an extraordinary genius, Da Vinci was often mocked for his unusual ginger hair. Targeted by gossip in Renaissance Milan, Leonardo appears in a 1495 drawing with red hair, seated at a desk surrounded by young men, with a wooden lyre at his feet and his father, Piero, behind him holding an anonymous denunciation document for sodomy.

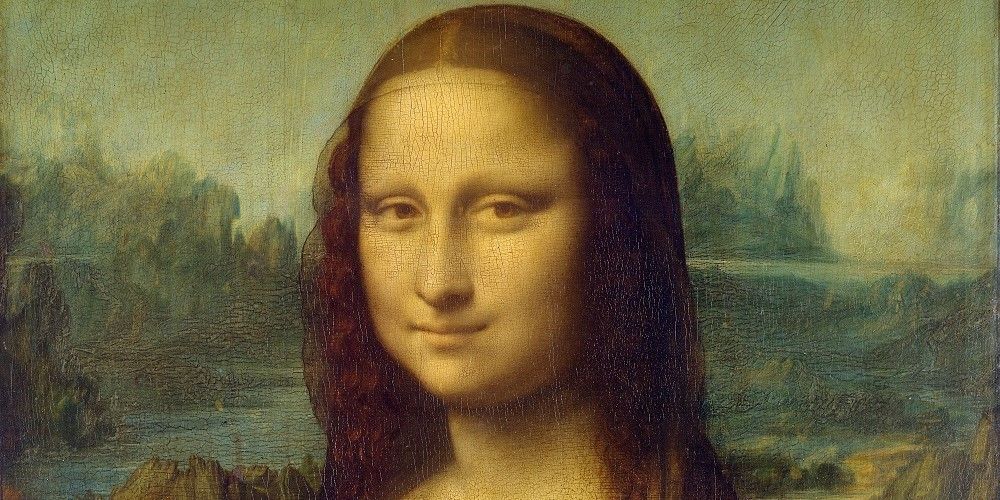

Whatever his favorite color, Leonardo masterfully combined colors in his works. Consider the marble-colored face of Ginevra de' Benci in the famous 1474 portrait, the red dress of La Belle Ferronnière housed at the Louvre, the brown, skin tones, and ochre of the Mona Lisa, the most famous portrait of all time. Leonardo also achieved immense plasticity in his drawings without using color, as seen in one of his most beautiful portraits, the so-called Head of a Young Woman, created on paper between 1478 and 1485 and preserved in the Royal Library of Turin.

2. How much is the Mona Lisa worth

Musée du Louvre

The Mona Lisa, also known as La Gioconda, is the most famous painting in the world, admired daily by 30,000 visitors—80% of those who purchase tickets to enter the Louvre. It is inevitable that such a masterpiece holds a record valuation: the portrait entered the Guinness World Records for the highest insurance valuation of a painting in history, set at $100 million in 1962, equivalent to $1.5 billion today. The Louvre took out this policy to cover a special exhibition from December 14, 1962, to March 12, 1963, which planned to tour the Mona Lisa from Paris to Washington and then New York. However, the policy was not enacted because the cost of maximum security precautions was lower than the insurance premiums.

Leonardo also holds another unique record: he created the most expensive painting ever sold at auction. Salvator Mundi, a half-length frontal depiction of Jesus Christ painted between 1490 and 1519, was rediscovered in 2005 after being considered lost for years. It was sold at Christie's in New York in November 2017 for $450.3 million, including commissions. The buyer was Saudi prince Badr bin Abdullah bin Farhan, who reportedly intended to display the artwork at the Louvre Abu Dhabi.

1. His masterpiece was destroyed

Not the Mona Lisa or the Vitruvian Man, not The Last Supper or The Annunciation, not even Lady with an Ermine or The Virgin of the Rocks—Leonardo da Vinci's true masterpiece is unknown because it was never completed. It was the equestrian monument for Francesco Sforza: in Leonardo's ambitious and colossal plan, it would have been the largest equestrian statue in the world. The work was commissioned in 1482 by Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, to honor his father Francesco, founder of the Sforza dynasty and Duke from 1452 to 1466.

Leonardo envisioned a gigantic rearing horse—a symbol of Sforza power and the elegance of the animal. The artist visited the ducal stables to study the best horses available in the city and spent years solving the static challenges of such a pose. For his colossal 7-meter-high statue, 100 tons of bronze were needed. When everything seemed ready to begin, after 17 years of preparation, those 100,000 kilograms were redirected to produce cannons to defend the Duchy from the invading French army.

About the author

Written on 15/04/2025

Alessandro Zoppo

From his mother's origins to his rivalry with Michelangelo: here are 10 trivia about life, death, and miracles of Leonardo da Vinci, the genius.