What the barbarians did not do, the Barberini did.

Rome is not simply a city for the Romans: it is much more. The universally recognised Caput Mundi mixes pure soul and authentic emotions. It is a place where official history is interlaced with ordinary people's lives.

Romans are people who can hardly keep quiet in a dialogue. No matter if they are in a bar, at the market, on the bus or in the square: they always complain about something while gesticulating theatrically and, often, in a blatant tone. Woe betide you if they don't say the last word! Without a doubt, if there is something that characterises the Romans, it is that touch of irony that never hurts. Over 500 years ago, this same attitude gave birth to the Talking Statues. Let's have a look at the 10 main curiosities linked to these singular monuments. Are you ready?

Explore Rome with Visit Rome Pass10. The Irreverent Voice of the Talking Statues

The birth of the Talking Statues matches almost exactly and scientifically the Rome of the Popes in the 16th century. The popes became holders of both temporal and spiritual power. This so-called role of the Pope-King was subject to fierce criticism by the Romans. What was the vehicle through which this form of dissent was possible? The Talking Statues, of course. Thanks to these singular monuments, people could criticise and ridicule the work of the popes with satirical signs posted anonymously at night. The following day, the population could learn the content of the protest. The essays in verse were not always polemical and pungent. They also were in the form of poems or dialogues full of humour. What is certain is that, in almost all cases, the addressee was the pope of the moment.

Of course, the perpetrators of such actions had to remain unknown to avoid many problems with justice. Freedom of thought did not exist at the time, but the voice of the Roman people was stronger than any authority. This is how the Talking Statues were born. Their "solid stone" embodied the hostility towards the overbearing nobles and corrupt clergy. Enveloped in the darkness of the night, the statues "spoke" and spared no one. The 6 Talking Statues all lie in the historic centre of Rome. They are symbol of the most genuine and irreverent Roman spirit, which does not bow its head before injustice and abuse. Let's see them one by one.

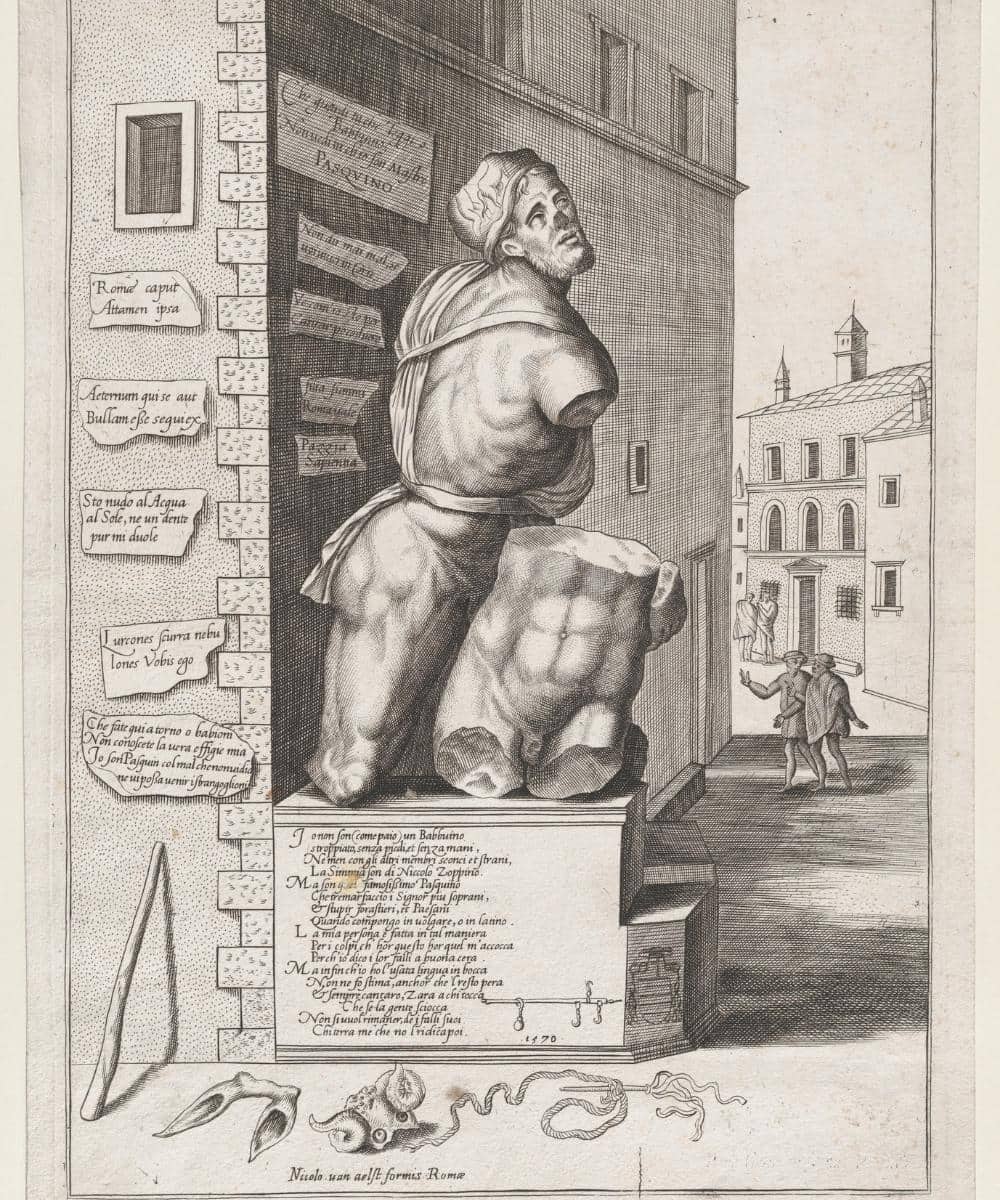

9. Pasquino, the first Talking Statue

Pasquino's talking statue locates in the square bearing the same name, at the corner of Palazzo Braschi (once called Orsini). It is behind Piazza Navona, in the historic District called Parione. Its discovery dates back to around 1501 when Cardinal Oliviero Carafa moved into Palazzo Orsini and ordered Bramante to renovate it. As part of the renovation work, an unidentified marble bust was brought to light, with no arms or legs, no nose, and rather hollow eyes. Many disputes arose about the real identity of the sculpture.

In all likelihood, it is a fragment of the Roman sculptural group (dating from the 4th century BC to the 2nd century BC) "Menelaus holding the body of the dying Patroclus". It was part of the decorations of Domitian's Stadium (today Piazza Navona). The Cardinal placed the statue where it is today, on a travertine pedestal. He also wanted to preserve the memory of his discovery with an epigraph: «Here I was placed by Oliviero Carafa in the year of 1501».

There is also much speculation about the name given to the statue. Maybe for the nearby Pasquino's tavern or the barber Pasquino, whose shop was in Parione. No less likely is the apparent connection with Pasquino the tailor, whose words against the Pope were sharper than his scissors.

Whatever the name's true origin, let's get to the point. Starting with the feast day of 25 April 1501, Cardinal Carafa had initiated a literary competition. The poems were posted to the statue itself, masked and adorned with drapes. This gave rise to the satirical sonnets in polemics against the Pope. However, in 1527, the dramatic sack of Rome definitively established Pasquino's role as the interpreter of popular discontent.

The Pope's guards didn't manage to track down those who posted their messages every night to denounce the misrule. Pasquino was the symbol of Roman freedom. Of course, the Church could not tolerate this situation and tried everything to prevent the circulation of these ideas. Hadrian VI considered throwing the statue into the Tiber, while Benedict XIII issued an edict condemning to death their authors. However, Pasquino kept on talking, and he was no longer alone.

8. Marforio, the Statue talking to Pasquino

Joining Pasquino was Marforio. This enormous bearded statue has changed location several times throughout history. Today, you can admire it by climbing the Capitolium steps and entering the courtyard of the Palazzo Nuovo. It is practically leaning against a wall adjacent to the Basilica of Santa Maria in Aracoeli. The name Marforio derives from Martis Forum as it was found near the temple of Mars in the Forum in the 16th century. The imposing statue depicts a male deity lying on his side on the edge of a pool, wearing a long cloak and holding a shell in his left hand. It could be a personification of the Tiber or the God Neptune and would seem to date from the first century AD.

What counts here is the "relationship" with Pasquino. The two of them had an intense and spicy dialogue. This is the reason why Marforio was considered Pasquino's sidekick. Their "long-distance chats" were subtle and intelligent. During the pontificate of Clement XI, the Pope was very interested in his home town, Urbino. Both Pasquino and Marforio had something to say.

Marforio: «Tell me: what are you doing Pasquino?».

Pasquino: «Oh, I'm looking at Rome, so that it doesn't go to Urbino».

Another famous satire was aimed at Pope Sixtus V's sister, who posed as a noblewoman and snob despite her humble peasant origins. Marforio, therefore, asked Pasquino: «Pasquino, why are you so dirty? Your shirt is as black as a coalman's». He replied: «What can I do? My washerwoman became a princess!».

7. The Babuino, or Pasquino's rival

Leaning against Palazzo Grandi, there is a statue called the Babuino. We are located near the Church of Sant'Atanasio dei Greci, between Piazza di Spagna and Piazza del Popolo. The figure is part of the decoration of the palace mentioned above. It probably represents a Silenus, a divinity between a man and a satyr. The name Babuino comes from its ungainly and grotesque appearance, in some ways similar to a monkey: the baboon. The lying silenus overlooked the basin of a fountain built at the behest of the noble Alessandro Grandi.

In ancient times the street where it was located was called something else, but the statue's features stimulated the imagination of the Romans. So, from Via Paolina, it became Via del Babuino (literally, Baboon street) . His famous satires, named Babuinate, competed with Pasquino precisely to mark his relevance to his "rival" in the nearby Piazza Navona. The protests also spread through graffiti that gradually covered the wall behind him. Following a major restoration, the graffiti was erased, and no trace of them now remains.

6. The Abbot Luigi, the headless Statue

After several displacements, the statue of Abbot Luigi is now in Piazza Vidoni, next to the Church of Sant'Andrea della Valle (between Piazza Navona and Largo Argentina). It is a Roman marble statue from the late imperial period depicting a man in office, perhaps a magistrate or orator, holding a scroll. It seems to have been named after the sharp-edged sacristan of the nearby Church of the Madonna del Santissimo Sudario. The inscription of his pedestal tells about the statue's satire: «I was a citizen of Ancient Rome | Now everyone calls me Abbot Luigi | together with Marforio and with Pasquino I conquered | Eternal fame in urban satires | I had offences, misfortunes and burial | But, here, I live a new and safe life».

Abbot Luigi spoke for the last time in 1966 when an act of vandalism deprived him of his head. However, thanks to restoration work, the trunk was given its head again in 2009.

«Thou, who didst steal my head,

bring it back immediately.

Otherwise, do you want to see it?

Like it was nothing

they send me to the government.

And that annoys me».

5. Madama Lucrezia, female representative of the Talking Statues

The only woman among the Talking Statues, Madama Lucrezia, stands precisely on the corner of Palazzo Venezia and St Mark's Basilica, a stone's throw from Piazza Venezia. The imposing marble half-bust, about 3 metres high and disfigured face, probably represents the goddess Isis or one of her priestesses. Again, it was the people who gave her the nickname. According to some, she was Lucrezia, Giacomo dei Piccini da Bologna's wife, who owned some properties in the square, as attested by a document dating back to 1536.

According to other sources, the statue was dedicated to Lucrezia d'Alagno. She was the beautiful lover of the King of Naples, Alfonso V of Aragon, and a favourite of Pope Paul III. The noblewoman spent the last years of her life in Rome, near Palazzo Venezia, in Piazza San Marco. Among the phrases "pronounced" by the statue itself between 1600 and 1800, we would like to mention the one dating back to 1799. During the Roman Republic, the rebellious people caused it to fall from its pedestal. Madama Lucrezia was face down and looking down. The following day an inscription appeared on its back, explaining the reason for its position: «I can't see any more».

4. The Facchino, the youngest of the Talking Statues

Initially, the statue of the Facchino (namely, the Porter) was on the main façade of Palazzo de Carolis, now known as Palazzo del Banco di Roma, on Via del Corso. In 1874, it was moved just around the corner to the nearby the Via Lata. Today, it still stands here, a stone's throw from the magnificent Piazza Venezia. It is the youngest of the Talking Statues, probably made in the second half of the 16th century. Of all six, it is the most beautiful sculpture, so much so that some attributed it to Michelangelo. According to others, it is the work of one of his pupils.

The sculpture represents an acquarolo, a man who used to sell water from public fountains and bring it to people's homes. It was a trendy profession in ancient Rome. The term facchino (porter) derives from her dress similar to that of the category of porters, but the barrel from which he pours water leaves no room for doubt. His face is disfigured because it is said that, resembling Martin Luther, children enjoyed hitting him with stones.

3. Three of the Statues are Fountains

The statue of the Facchino, the waterman holding the barrel from which he pours water, is set in a small fountain. It was made of light marble in 1580, during the pontificate of Gregory XIII. It was probably commissioned by the Corporazione degli Acquaroli. It is fed by the Acquedotto dell'Acqua Vergine.

More monumental and conspicuous is the large fountain incorporating the statue of Marforio. The colossal statue of the river deity is placed in the central niche set into the back wall of the building. Three large grey granite columns, with a relief frieze of Egyptian priests, lead from the nearby sanctuary of Isis and Serapis in Campo Marzio.

The Babuino fountain was built by a private individual but intended for public use. It consisted of a basin dating from Roman times, made of grey granite, from which water gushed out through a simple straw. Over it, the statue of Babuino lying on a cliff watches over the fountain.

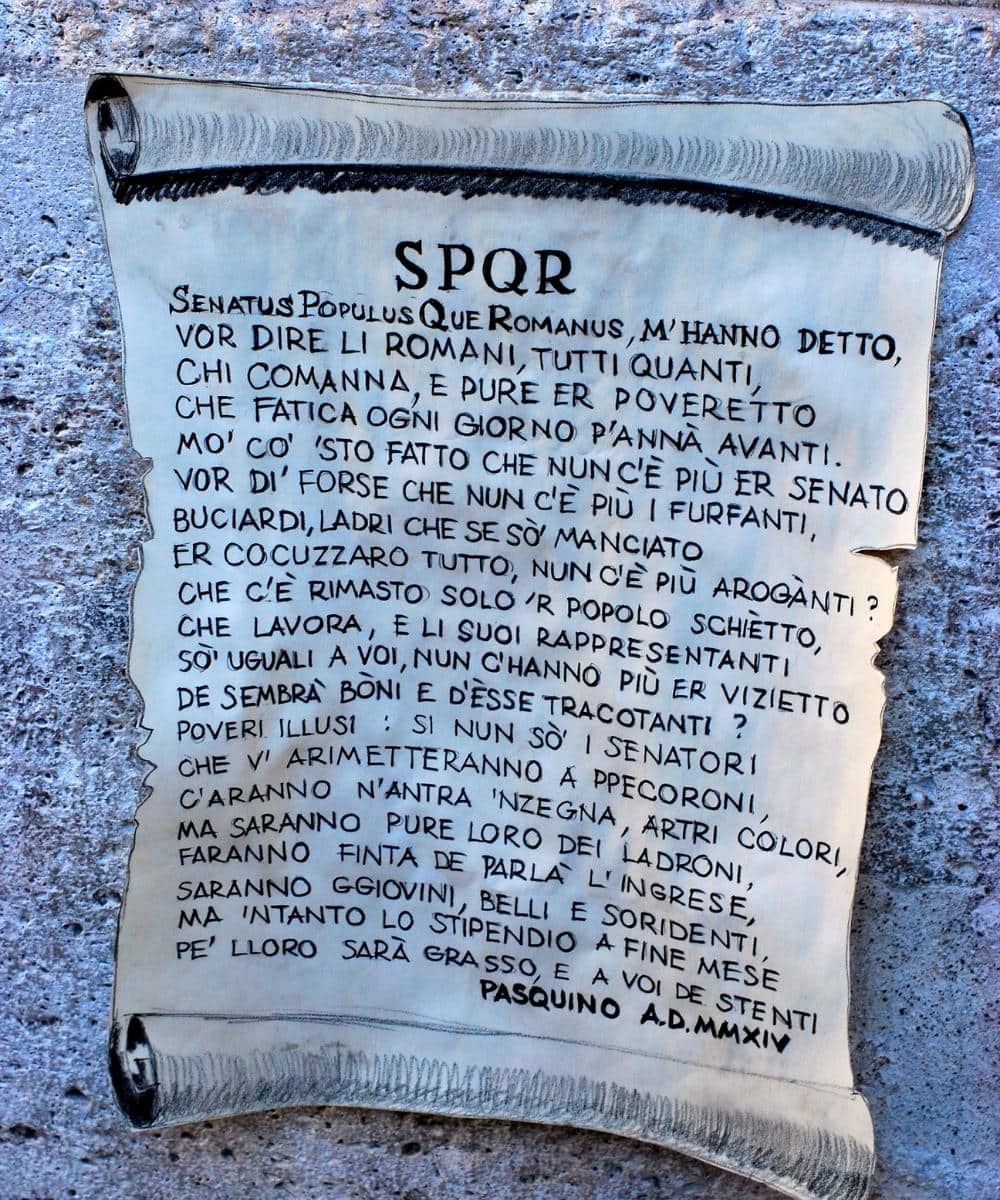

2. What does the term Pasquinate mean?

As you can easily guess, the word Pasquinate originates from Rome's most famous and first talking statue, Pasquino. By extension, the term was then associated with any anonymous expression of protest through notes affixed to the statues. These messages were posted in the middle of the night to be visible to the entire population the following day.

They were satirical essays of varying length but generally short, written in verse or prose. Typically, they were addressed to the popes, the Roman Curia (namely the administrative institutions of the Holy See) or anyone who deserved to be blamed because of bad or immoral actions. The first ones appeared in Latin, then in vernacular Italian and finally in Roman dialect. Pasquino, therefore, became the symbol of the people's political satire in an irreverent, mordacious and spicy tone.

1. The most famous satyrical verses in History

Among the most famous Pasquinate (satires affixed on the statue), the first one dates back to 13 August 1501. Referring to the bull on the papal coat of arms, Pasquino said to Alexander VI Borgia: «Preedixi tibi papa bos quod esses», Here, three translations from Latin are possible:

- I predicted that you would be an ox pope

- I predicted, Oh ox, that you would be pope

- I predicted, Oh pope, that you would be an ox.

Note: changing the position of the comma, Pasquino alludes to an image of the pope, who was not popular with the Romans. None of the three possible translations offers a good picture of the Pope.

Pasquino's comment on the election of Paul V Borghese on 16 May 1605 was as follows: «After the Carafa, Medici and Farnese families, now it's the turn to enrich the Borghese family». (Note: in Italian, the rhyme plays a fundamental role). It was somewhat open and blatant criticism of the pomp and circumstance of the popes and their respective families.

Similarly, also the pope Urban VII Barberini was fiercely attacked. Following the Jubilee of 1625, the Pope imposed heavy taxes (gabella) to cope with the unsustainable war effort. Pasquino could not keep quiet even this time: «Urban VIII with the beautiful beard after the jubilee imposes the gabella». (Note: in Italian, the rhyme plays a fundamental role)

The same Urban VII, then, "took" bronze beams from the pronaos of the Pantheon, which would later melted down to make St. Peter's Baldachin and the cannons of Castel Sant'Angelo. Once again, the sentence of the Talking Statue was not long in coming: «Quod non fecerunt barbari fecerunt Barberini». Here, the message referred to Barberini's destruction, which caused more damage than a barbarian invasion.

The series of Pasquinate is unending so that we will stop here. Just remember; throughout history, no one has escaped the severe and implacable judgement of the talking statues, the true people's voice!

A whole new way to explore Rome.

About the author

Written on 29/12/2021

Alessandra Festa

Have you ever heard of Talking Statues? Let's discover together secrets and curiosities that few people in the world know!